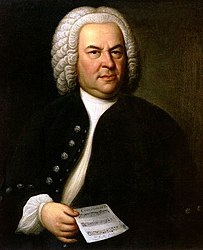

Johann Sebastian Bach and George Friederic Handel, two of the greatest protagonists of music of all time, united by extraordinary creative and performing genius, both born in Germany in the same year, 1685, also shared the sad fate of the gradual extinction of their sight that led to their blindness. But there is more. The two composers who, though contemporaries, never had the chance to meet, were the unfortunate patients of the same eye doctor, Dr. John “Chevalier” Taylor (1703-1772).

But who was he?

Trained in a prestigious English medical school, John Taylor, was one of the first to devote himself exclusively to eye surgery and was the first to describe keratoconus and to envisage the surgical correction of strabismus. He shared his knowledge in several publications whose scientific value was recognized even outside English borders. Taylor became so famous that he was able to begin a career as an itinerant surgeon through Europe, Russia and as far as Persia, alternating between treating patients of royal lineage and reading at the most prestigious scientific institutions.

But, incredibly, alongside the glories of a glittering career, disturbing tales emerge from the chronicles of the time describing a greedy physician of bizarre behavior, what we would in essence call today a true charlatan: Taylor lent his services only in return for lavish fees and, in his travels, advertised his arrival in every town with posters and leaflets. His carriage was decorated with paintings of eyeballs and the motto “qui dat videre dat viver” (he who gives sight gives life). He plied his trade in the loudest way, drawing crowds to the town squares and then leaving before the patients had time to remove their bandages!

Taylor’s lies

Nor did he fail to celebrate his adventurous exploits in an autobiography in which he “celebrates” two of his most illustrious patients, precisely Bach and Handel: “…I have seen a vast variety of singular animals, such dromedaries, camels &c and particularly at Leipsick, where a celebrated master of music, who had already arrived to his 88th year, he received his sight by my hands; it is with this very man that famous Handel was first educated, and with whom I once thought to have had the same success, having all circumstances in his favour, motions of the pupil, light etc but upon drawing the curtain, we find the bottom defective, from a paralytic disorder… ”.

In other words, a big pile of baloney: Bach, certainly the “master of music” to whom Taylor refers, had not reached the age of 88 (in fact, he died at the age of 65), as mentioned Bach and Handel never met, and, most importantly, neither received any benefit from Dr. Taylor’s treatment!

But let us try to understand what really happened.

It is certain that Bach’s eyesight had deteriorated greatly in the last period of his life, so much so that the authorities of St. Thomas Church, where he had held the position of Maestro di Capella since 1723, held an interview with Gottlob Harrer to succeed Bach in the event of his sudden departure.

At the time, Bach was working on the Art of the Fugue, but he never began the last of the planned series of twenty and interrupted his work in the middle of the ”diaciannovesima”.

Exasperated by the serious condition of his eyesight, Bach also fell into the net of the great crowd-pleaser and was persuaded to have an operation when Taylor arrived in the city of Leipzig in the spring of 1750. The first operation took place between March 28 and 31, 1750; after a brief improvement, the composer’s eyesight deteriorated again and a second operation, performed between April 5 and 7, was necessary.

The couching

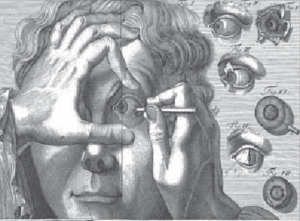

Most likely Taylor practiced couching in Bach, the first surgical procedure for cataracts to which Taylor had devoted no less than nine pages in his 1736 book “Cataract and Glaucoma.” In this operation he would make a small incision near the limbus. With a needle he opened the posterior capsule and dislocated the lens inferiorly.

The operation had to be repeated a week after the first one was performed, probably due to anterior dislocation of the crystalline lens and, likely resulting in pupillary blockage and glaucoma. These surgeries, already in themselves burdened with a high risk of failure, were followed by postoperative treatments that were disturbing, to say the least: Taylor’s general approach included bloodletting, laxatives, local application of pigeon blood medicine, pulverized sugar, baked salt, Peruvian Balsam, cassia pulp, and so on. After surgery, the patient had to maintain, for several days, a bandage in which a cooked apple or coin was inserted. In cases of severe inflammation Taylor prescribed large doses of mercury, which, moreover, he was already using, probably as an antiseptic, during surgery.

The surgical operation on Bach

It is not known whether Taylor operated on one or both of Bach’s eyes but, taking into account that he was right-handed, his practice was to always operate on the right eye, even if the right eye was the healthy one!

True, at that time physicians had no concept related to asepsis, the only anesthetics were alcohol and opiates, and surgeries were performed with patients sitting in a chair, tenaciously restrained by an assistant. For their part, patients had very few expectations. They simply knew that if they put themselves in the hands of an eye surgeon perhaps they would have some chance compared to doing nothing.

In fact, Taylor’s conduct, especially his practice of always operating on the right eye and the application of bandages, was already criticized by some surgeons of the time but Taylor cared little, considering that the patient usually removed the bandage only 5-6 days after surgery when Taylor had already left for another destination.

It is then to be considered that Bach was operated on by Taylor at the time when modern cataract surgery, codified by Jacques Daviel in 1756, practiced by extraction of the lens, was beginning to spread, with gradual abandonment of couching, which was, however, still practiced for about a century and is still in use today in parts of Asia and Africa.

In fact, after Dr. Taylor’s “services,” Bach was found to be blind and died only 4 months later. No documentary evidence is available to establish with certainty what was the cause of the composer’s death-so many hypotheses have been formulated over the centuries! – but beyond the evidence, it is difficult to think that the interventions and procedures Taylor put in place were unrelated to the exitus.

What really happened to George Frideric Handel

Handel’s medical history was much longer than Bach’s because his eyesight began to deteriorate beginning in 1751. In February of that year he was forced to suspend the composition of the oratorio Jephtha, noting on the score that he was unable to continue because of the “weakening” of vision in his left eye.

The following spring he had himself examined by Dr. Samuel Sharp, of the same school as Taylor, who diagnosed him with “incipient gutta serena,” that is to say, in today’s terms, a principle of blindness of unknown origin, ruling out the presence of cataracts.

Handel nevertheless managed to resume activity and complete the Jephtha, but with his sight now almost completely lost in the left eye and severely declining in the right, he decided to turn to Dr. William Bromfield, then surgeon to the Princess Dowager of Wales, who performed his first couching surgery in November 1752.

Handel seemed to have regained some of his sight, but chronicles of the time described him as blind by early 1753. However, at that time he was still able to write, conduct, and play the organ, and although he did not compose new works, he was able to revise some older works.

Handel suffered terribly from the reduction of his eyesight, which he described as “…worse than misery, old age or chains...” and it is well understood why he did not hesitate to have surgery several times and probably the last one at the hands of Taylor.

The legend of Dr. Taylor’s death.

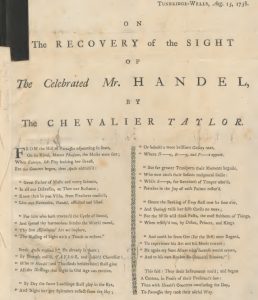

In this regard there is evidence that Taylor and Handel in August 1758 both stayed in Turnbridge Wells. It was in that town that the writing of a terrible poem, dated August 15, 1758, later published in the London Chronicle of August 24, 1758, in which Taylor himself celebrates his extraordinary ability to restore Handel’s sight occurred. In the poem Euterpe calls Apollo and Aesculapius to help the blind Handel but Apollo replies that Aesculapius is not necessary because Dr. Taylor will do it (!). The poem and the reference to the episode in Taylor’s autobiography represent the only documentation that supports the hypothesis that Handel was “cured” by Taylor.

In any case, Handel, as well as Bach, never regained his sight and he too died only a few months later, in April 1759.

Again, there is a lack of certain elements to attribute clear responsibility to Dr. Taylor in Handel’s tragic fate, and not even the mere “chronological criterion” can help in this regard. What is certain is that Dr. Taylor’s reputation leaves little doubt that if he indeed laid a hand on Handel’s eyes, it was not beneficial!

Legend has it that Dr. Taylor died in 1772, obviously blind!

Hallelujah

Well Hallelujah!!!

Let us remember, however, to stand up when we hear the Hallelujah from Handel’s oratorio “Messiah” as the King of England, George II, did when he first attended it. Since then, in homage to the immortal composition, when it is performed in concert, the whole audience stands up.