The dramatic chronicle of a distinguished patient and a death foretold.

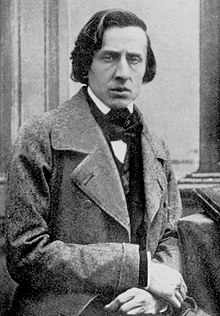

Resuming our journey on the illnesses that have inexorably marked the lives of some great musicians, we retrace the dramatic story of Frederic Chopin, the celebrated Polish composer forced to share his short existence with “consumption”.

Beginning in the 17th century, when the tuberculosis epidemic swept across Europe, the “Great White Plague” found the high population density and poor hygienic conditions in many cities to be favorable factors for massive spread. Fear of contagion was very strong and even anatomists refused to perform autopsies on patients found to be suffering from “consumption.” As early as 1650, tuberculosis became the leading cause of death, and dying from tuberculosis was considered inevitable.

On the other hand, the treatment of tuberculosis up to the end of the 19th century essentially consisted of a combination of rest, good nutrition, cough mixtures commonly containing opium, bloodletting (up to 250 ml two or three times twice a week), emetics, laxatives, as well as mercury or antimony. For those who are able, there is a prescription for stays in regions with a mild climate and in thermal areas. Thus, very little effective weapons for such a severe disease.

It should also not be forgotten that, not infrequently, doctors in the scene are outright quacks and that even those who are qualified are inclined to deny the diagnosis until the disease has reached a very advanced form, sometimes ignoring the most obvious physical symptoms. This should not be surprising since such a diagnosis could have negative consequences on the social and economic position of the patient.

Nor would these spare even such an illustrious figure as Frederic Chopin.

Frederic Chopin

Fryderyk Franciszek Chopin was born in Zelazowa Wola, near Warsaw, on February 22, 1810. He has three sisters and one of them dies of tuberculosis when he is 17. It has been speculated that Emilia’s sudden death, only a few months after the onset of the disease, was hastened by the crude medical treatments given to her. It will probably be the memory of this episode, and of the unnecessary suffering endured by his sister, that will mark Chopin’s approach to the disease when, a few years later, he is found to have it.

It was in 1835 in Paris that Chopin had his first episode of hemoptysis. At that time he shares lodging with Dr. Jan Matuszynski, his childhood friend. Matuszynski must have noticed that his friend’s health was not good because he recommended periods of stay in spa areas and rest in the countryside. It seems that already by that time Chopin had been working on an accurate assessment of his health, consulting several doctors in Paris, but without receiving specific guidance. After only a few weeks of bed rest, Chopin resumed his busy life of composing, teaching and concertizing.

During a flu epidemic in the winter of 1836, Chopin again experiences hemoptysis. He consults Dr. Pierre Gaubert, a local allopath and friend of George Sand. Gaubert, after an examination, rules out the possibility of consumption, suggesting a “simple” bronchitis.

Dr. Gaubert advises Chopin of the mild climate of southern Europe. So Chopin moves with George Sand to Palma de Mallorca. Contrary to expectations Chopin’s respiratory symptoms worsen: the house by the sea is not heated and the fumes from the brazier do not help his cough. New medical consultations are necessary, and this time no less than three doctors confirm the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis, recommending bloodletting and blistering patches, which Chopin refuses. Chopin is forced into quarantine and, in his isolation, despite the lack of a suitable piano – the Pleyel piano will arrive just days before his escape from the island – he composes Opus 28 and writes 24 preludes. News of the contagious disease spreads quickly among the island’s population, which reacts badly. Everyone avoids contact with the couple, who are forced to move to a villa in the countryside, several kilometers from the sea. Their life is made more difficult every day, with food prices becoming more and more expensive for them. Soon even the owner of the villa asks the couple to leave as soon as possible, charging Chopin for the cost of sanitizing the house. The two find refuge in the Vallemosa monastery – where a museum dedicated to Chopin is now housed – for the time it takes to organize the return trip, which is also far from easy.

The couple must reach the port in a wagon because no one dares to rent them a carriage. On the journey Chopin stops in Barcelona and in the cost of the hotel he is charged for his bed, which, by authority order, must be burned.

Once in France he is advised not to return to Paris but to stay in the southern regions. Persistent pulmonary symptoms force him to seek new medical consultations, with mixed results.

In Nohant, it is Dr. Gustave Papet who examines him. The doctor reassures him because, in his opinion, it is certainly not tuberculosis but chronic laryngitis. Refreshed by the new diagnosis in 1839 Chopin returned to Paris where he resumed teaching, although his health condition is far from good. He is weak, pale, and continues to cough despite taking opiates. Over the next 5 years, attacks of fever are frequent, coughing worsens, and hemoptysis is recurrent.

Following the end of his relationship with George Sand, Chopin’s health deteriorated further, but he continued to compose and give concerts. Because of his poor financial situation and the outbreak of the February Uprising of 1848, he is encouraged to leave Paris for London and Scotland, accompanied by his student, Jane Stirling, and her sister. During the trip he meets Dickens and gives several concerts, one of them in the presence of Queen Victoria.

In London he consults other doctors, but gets little advice and no relief. Also visiting him is the queen’s physician, Dr. Clark, who prescribes rest and an immediate return home. Chopin disregards the doctor’s instructions as economic necessity dictates that he continue the tour: everywhere there are friends and admirers waiting for him.

The strain for the concerts, however, is increasingly great for him and the English climate unbearable. Chopin is increasingly thin and debilitated, constantly wracked by coughing. For his 5’7″ height he now weighs only 100 pounds.

On his return to Paris in the fall of 1849, he turns desperately to other doctors but soon finds himself saying, “Everyone feels me, everyone palpates me, but no one can help me…. “

Finally, only four months from his death, he turns to Dr. Jean Cruveilhier, France’s leading expert on tuberculosis, who has no doubts about the tubercular origin of his health problems. But by then it is really too late to help him. Chopin is reduced to skin and bones, his cough and dyspnea no longer leave him, he has recurrent diarrhea and edema in his ankles. By Sunday, October 16, Chopin is bedridden, and at his home in Place Vandome it is a constant coming and going of Parisian High Society who come to pay their respects to the great composer: unlike Mozart, who died in the saddest solitude, Chopin’s imminent passing becomes an unmissable social event!

Chopin, only 39 years old, passed away at 2:30 a.m. on Oct. 17, 1849, with Dr. Cruveilhier, his sister Ludwicka and some friends at his bedside.

Post mortem

“The earth is suffocating…Swear to convince them to cut me down so that I will not be buried alive…” says Chopin to one of the sisters on his deathbed.

In compliance with his wishes, the body undergoes an autopsy, which is performed by Dr. Cruveilhier himself three days after death. The manuscript describing the autopsy was never found, probably destroyed in the great Paris fire of 1871.

Some information about the outcome of the autopsy is contained in Jane Stirling’s correspondence with Franz Liszt, in which she quotes Dr. Cruveilhier as saying that “…the autopsy did not reveal the cause of death…however, he could not have survived…several pathologies…enlarged heart…did not reveal pulmonary tubercolosis….“. In fact, Stirling’s words must be viewed with caution as it is possible that she may have given a different version of what the doctor actually reported to her, and this was out of fear that it might be thought that she and family members might be suffering from tuberculosis.

In any case, it appears that this was only a partial autopsy, limited to dissection of the chest. The body is then embalmed and displayed in the crypt of the Sainte Marie Madeleine church for the final farewell. The funeral is held a full 13 days after the death: 13 days are in fact necessary to obtain permission for women to enter the church – then prohibited – whose voices were needed to intone Mozart’s Requiem, performed at Chopin’s express wish by the Orchestra and Choir of the Paris Conservatory. Organist Lefebure-Wely also performs the two preludes from Op. 28 (No. 4 and No. 6). Finally, the Funeral March from the second piano sonata accompanies his burial.

Chopin’s body rests in Paris’ Père-Lachais Cemetery between Bellini’s and Cherubini’s tombs. Ironically, the funeral sculpture placed on the tomb is carved by George Sand’s husband, Clesinger, who also made the funeral mask and the cast of the hands, both of which are now in the Chopin Museum in Warsaw.

Chopin’s heart

Resting in the Père-Lachaise tomb is not the composer’s heart. After autopsy examination, the organ is in fact laid in a jar of cognac that is entrusted to his sister Ludwika. Sneaking past Russian guards (Russia ruled Poland at the time), the relic reached Warsaw where it is laid in a column of the Church of the Holy Cross.

During the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, the container with Chopin’s heart is claimed by a high-ranking SS officer who claims to be a great admirer of him. Stored in the general headquarters of the German high command, the canister is returned to its church of origin only at the end of World War II.

In 2017, Polish scientists had the opportunity to view the jar and examine it, but were not allowed to open it. The findings of their investigation were outlined in an article published a few years later in the American Journal of Medicine. According to the authors’ description, the organ is immersed in an amber liquid that they assume to be cognac; it is covered with white fibrous material (“frosted heart”) and small nodular surface changes are visible, which are interpreted as typical of a tubercular manifestation. Also ascribed to the same origin are some areas of orange-colored sub-endocardial hemorrhagic suffusion. The heart is also found to bear the signs of autopsy dissection but considerable dilatation of the right ventricle is appreciable.

These are the findings on the basis of which the authors posit tuberculous pericarditis, a rare complication of chronic tuberculosis, to which the composer’s death is ultimately to be ascribed.

Of an entirely different opinion are the authors of a commentary note directed to the same scientific journal: the fibrinous deposits on the surface are traced to the prolonged action of a fixation fluid with a high alcohol content, the nodular changes at the epicardial site do not allow a diagnosis of the tubercular origin in the absence of histological investigations, and even the “hemorrhagic” infiltrates, characterized by a peculiar orange pigmentation, can be interpreted as fixation artifacts. Nor can the extent of dilatation of the right ventricle be assessed since none of the measurements that can be performed on the organ are reported.

The diagnosis of pericarditis tuberculosis is thus far from confirmed. For those in the field, there remains a sense of an unfinished investigation in the face of the many possibilities that today’s forensic sciences can offer to reach a definitive diagnosis based on objective evidence. Without altering organ integrity, for example, radiological examinations could offer interesting morphological information while in-depth genetic investigations could also be useful in writing a definitive word on the hypothesis, put forward by many, that Chopin’s pathological picture is to be ascribed to hereditary cystic fibrosis from Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

In truth, beyond the opportunities that modern science is able to offer, there is much that can be gleaned from the timely historical reconstruction of Chopin’s life to support the recurrence of pulmonary tuberculosis, likely contracted by the composer in his youth, that is, at the time of his sister Emilia’s illness and death. From such a perspective, what is striking is Chopin’s long survival of this disease, many decades before Koch, in 1882, identified the pathogen. Some scholars are inclined to believe that credit, in this regard, should be given to Chopin’s affluent conditions, with constant recourse to medical consultations, being able to stay in mild-climate environments, but above all, to his reluctant attitude to undergo the debilitating treatments of the time, which, as we have a chance to see in Paganini’s clinical affair, contributed to accelerating the exitus rather than to saving it off.

In any case, as with other authors, retracing Chopin’s life story, so marked by illness, inevitably leads one to wonder about the effects that such a condition may have exerted, positively or negatively, on his compositional fecundity and inspirational execution. The notion then that tuberculosis is associated with particular artistic abilities has ancient origins. For the Greeks it was the spes phtisica and indicated a special creative energy associated with a pronounced artistic sensibility. Perhaps, then, it is from the much-suffering pathology that inspired Chopin’s feeling and composition?

Questions for which there is no answer, just as there is no relief – it has already been said about Mozart – for the deep regret for a life that was prematurely extinguished but that “still possessed a powerful creative power that could not be fully expressed.”