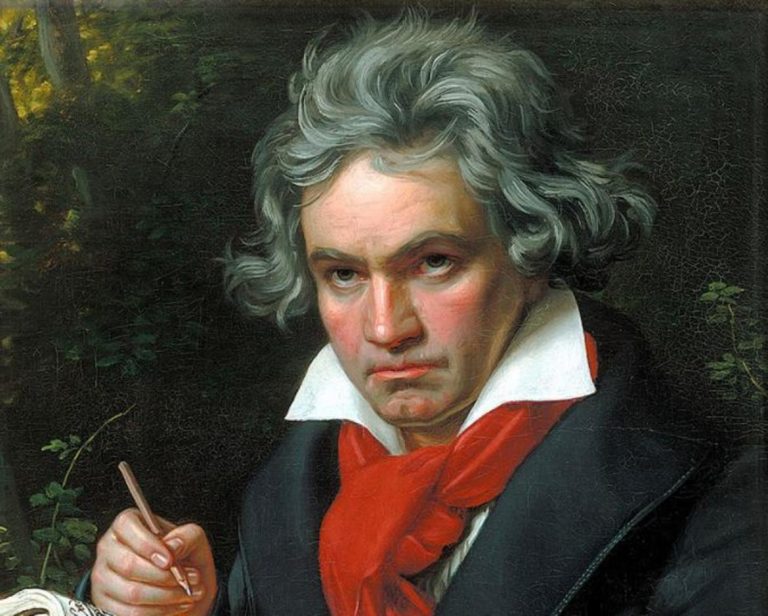

For many to call to mind the image of Beethoven is to evoke the thick lion’s hair that frames the composer’s grim and proud face painted by Joseph Karl Stieler in 1820. Some locks of that hair were separated from the composer’s mortal remains and had a fascinating fate of which we tell you about in this article.

The passing and the funeral

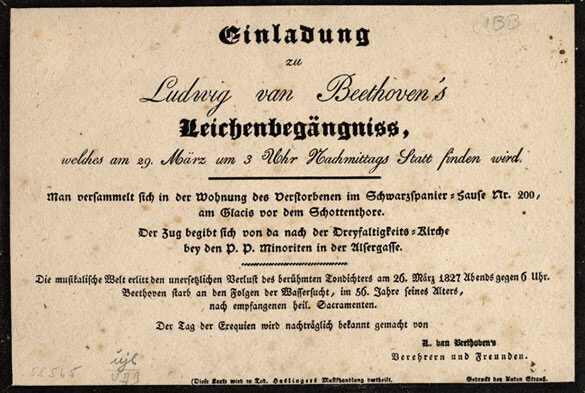

Beethoven passed away in Vienna on a stormy March afternoon in 1827.

An autopsy was performed the following morning, and in the afternoon the body was displayed for a final farewell. Unlike with other composers, (see articles on Mozart and Paganini) Beethoven received an impressive tribute, and his funeral was indeed lavish.

As a respectful tribute Vienna came to a halt for three days. Twenty thousand people and hundreds of carriages paraded in the wake of the coffin. The funeral oration was entrusted to the poet Franz Grillparzer, who celebrated Beethoven’s entrance into immortality as follows: “For this there have always existed poets and heroes, singers and enlightened ones of God: let the miserable ruined mortals turn toward them, mindful of their origin, and of their goal.”

To soundtrack the solemn tribute were performed the Equals for brass transcribed for choir on the words of the Miserere and, in two suffrage masses, Mozart’s Requiem and Cherubini’s Requiem for mixed voices.

The body was then buried in Wahring Cemetery, northwest of Vienna, where Beethoven’s grave was joined only a year later by Schubert’s. In 1863 both coffins were later moved to Simmering cemetery where they still rest today along with other distinguished musicians-Gluck, Salieri, the Strauss father and son, Brahms, Schoenberg, Ligeti.

On the trail of Beethoven’s hair

If, therefore, much of Beethoven’s mortal remains rest in Vienna’s Musicians’ Cemetery, different fates have befallen many of the locks of his hair. For some of these, through complex and careful historical investigations, it was possible to establish the long path that, over the centuries, led them to the most diverse places in the world.

Anton Halm’s lock of hair

Pianist Anton Halm reported that in 1826, while working with Beethoven on the Grand Fugue Op. 133, he asked the composer’s factotum, Carl Holz, if he could have a lock of the master’s hair as a gift to his wife. In the 1800s, asking for a lock of hair as a gift as a “souvenir” was not considered as bizarre a custom as it might appear today. So a few days later, obviously for a fee, the hair was sent to Halm. Soon, however, he was able to discover that it was goat hair.

When the work of arranging the Fugue was finished, Halm brought the sheet music and also the false lock to Beethoven. The composer, enraged that his friend had been the object of a real scam, promptly cut a lock off his head and handed it to him, declaring that this one was definitely genuine.

A small oval frame containing the gray-brown hair given to Anton Halm was auctioned at Sotheby’s in June 2019 and sold for £35,000.

Ferdinand Hiller’s lock

Upon hearing the news of Beethoven’s death, friends, admirers and onlookers poured into the Black Spaniards’ House, where the funeral chamber had been set up, to pay their respects to the body and, on the occasion, to procure some relic-locks of the deceased’s hair. Among them was the young music student, then 15 years old, Ferdinand Hiller, who had come from Cologne to accompany his teacher, J.N. Hummel, a friend of Beethoven. The boy grabbed a lock of the composer’s hair, which he then took with him to Paris, where it was enclosed in a glass medallion with a wooden frame.

Ferdinand kept the precious heirloom with him throughout his life and, shortly before his death, made a gift of it to his son Paul. The latter took the utmost care of the extraordinary legacy he received from his father, so much so that in 1911 he took care to have it restored by a craftsman so that the hair would remain perfectly preserved in the small shrine. But it was upon Paul’s death in 1934 that all trace of the locket was lost and, with it, the Hiller family.

We know that Hiller was of Jewish descent. In the early 1930s, writers, painters and musicians were the first Jews to leave Germany to flee the Nazi fury. In all likelihood, the Hiller family, like other Jewish artists’ families, was forced to take refuge in Denmark since it was in this country that, in 1943, the medallion reappeared in the hands of Kay Alexander Fremming, a doctor from Gilleleje. The most plausible hypothesis is that Dr. Fremming, who did much to welcome and expatriate Jewish refugees to neighboring, neutral Norway, may have received the medallion as a gift from a refugee as a gesture of gratitude.

The relic then passed into the hands of Michele, Dr. Fremming’s adopted daughter. In 1994, realizing the value of the relic and pressed by financial difficulties, Michele was forced to part with it and entrusted it to Sotheby’s so that this lock of hair could also be sold at auction. It was won by four members of the American Beethoven Society: Dr. Alfredo Guevara (a urologist), Mr. Ira Brilliant (a wealthy collector of Beethovenian memorabilia), Dr. Thomas Wendel and Mrs. Caroline Crummey, for a combined sum of $7,300.

Part of the lock hair that belonged to Ferdinand Hiller is now kept at the Beethoven Center in San Jose, California.

Other locks, likely those among the many removed during the wake, are still held today at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., the University of Hartford in Connecticut, the British Library in London, the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna and the Beethoven-Haus in Bonn.

Beethoven’s hair and forensic science

Beyond the fascinating historical implications, for anyone interested in forensic science Beethoven’s locks of hair cannot fail to appear as an extraordinary opportunity to learn more about the composer’s state of health.

In truth, the buyers of the Hiller lock did not attend the auction with this intent. For them the lock of hair represented a prestigious heirloom of their idol to bring back to the United States and to add to the many already acquired. It was only when the medallion reached their hands that they realized its real historical value. After long and thoughtful evaluation, they decided that the lock would be divided in proportion to the contribution made for the purchase.

Seventy-three percent of the hair would be destined for the Beethoven Center and preserved for future investigation, while the remaining portion would remain in Dr. Guevara’s possession. The latter immediately decided to take the path of scientific research and form a team of forensic experts-the best forensic experts! – to check the state of the sample and evaluate the possible investigations that were practically feasible. The identification of the experts took several months.

In December 1994, in the presence of a forensic pathologist, Dr. Richard Froede, and a forensic anthropologist, Dr. Walter Birkby, the case was opened and as many as 582 hairs were counted. Some of them exhibited hair follicles thus reassuring the experts that the DNA search could be performed. According to the arrangements 422 hairs went to the Beethoven Center and 160 to Dr. Guevara.

Of the latter, 20 hairs were initially sent for toxicological investigation to Dr. Werner Baumgartner, the expert who a few years earlier had demonstrated the presence of morphine in the hair of poet John Keats. But in this case, contrary to expectations, the analysis revealed no traces of morphine. So, although gravely ill and certainly in severe pain, in the last months of his life Beethoven had rejected palliation in order to maintain lucidity and with it the possibility of imagining new future musical projects until the end of his days.

The investigation was continued by Dr. William Walsh of the Health Research Medical Center in Naperville, known for having examined the hair of Charles Manson and many other American criminals. Walsh’s examination showed that, despite time, the hair had preserved its structure intact, and the possible presence of metals could be effectively investigated in terms of actual intake during life, without the doubt of post-mortem contamination. So it was Dr. Walter McCrone, of the McCrone Research Institute in Chicago, the same man who had studied Napoleon’s hair and the Holy Shroud, who carried out this further investigation.

But even in this case it was a negative result that was surprising: the absence of mercury. Mercury was the main medicine for syphilis in the 1800s, and the investigation was worthwhile in ruling out the possibility that Beethoven’s known health problems could be traced back to this pathology, as had been speculated by many.

There was one positive result, however: Beethoven’s hair documented a lead content 42 times higher than controls. But then did Beethoven die of lead intoxication, and is it to lead that the deafness and all the other afflictions that plagued him throughout his life can be traced?

The solution to the enigma

Since 1995, when the results of research on Beethoven’s hair were made public, this question has continued to haunt the minds of enthusiasts but, to date without a comprehensive answer.

While some authors believe that Beethoven chronically took lead for much of his life-which would account for the deafness (complete as early as 1817) and many other symptoms attributable to saturnism, including the angry outbursts and bizarre behavior-others lean toward acute intoxication attributable to the therapies given to the composer before his death (C. Reiter, 2007).

These positions have come under intense criticism. In addition to pointing to the common presence of lead in many everyday objects (plates, glasses, etc.) and even in wine-known not to have been disdained by Beethoven-different authors emphasize the relevance of autopsy findings that, objectively and without the need to bring lead into the picture, document a clinical picture suitable to justify the symptoms manifested by Beethoven throughout much of his existence and to clarify the cause of his death (J. Eisinger 2008, Fellin 2019).

The autopsy-perhaps performed in response to Beethoven’s wishes expressed in his Heiligenstadt Testament in which he asked for light to be shed on the reasons for his such poor health-was performed by Dr. Johann Wagner inside the composer’s apartment. At Wagner’s side was the young assistant Karl von Rokitansky, destined to be one of the founders of modern pathological anatomy (this was the first of 59,786 autopsies for him).

The autopsy findings were described in detail in a text written in Latin that remained unavailable for many years. It was only in 1970 that it was found in the Museum of Pathological Anatomy in Vienna. Translations of the original report are also available in German (Ignatz von Seyfried, Beethovens Studien im Generalbass, Wien, 1853) and English (PJ Davies 2017).

The autopsy picture described documents an organism prostrated by decompensated macronodular liver cirrhosis (ascites, portal hypertension, splenomegaly) and bacterial peritonitis, concomitantly with chronic pancreatitis, gallstone stones, chronic pyelonephritis, nephrolithiasis, and hydropyonephrosis (E.J. Pauwels 2021, Fellin 2019).

Ultimately, Beethoven’s hair has certainly reopened the game but the conundrum is far from solved.

And on closer inspection, beyond the many elements that forensic science has been able to identify and will likely be able to track down in the future, it just seems that there can be no universally acceptable explanation for what disease might have allowed, despite himself, the expression of such creative genius and what cause of death challenged Beethoven’s immortality.

For those who wish to investigate in greater detail the chronicle of the adventurous events of the “Hiller lock,” we recommend reading the book “Beethoven’s hair: an extraordinary historical odyssey and a scientific mystery solved” by Russell Martin and watching the documentary inspired by it by director Larry Weinstein.