Abstract

On the cause of Mozart’s death, as often happens with great men who have marked the history of mankind and died prematurely, a mystery continues to hover that never ceases to fascinate music lovers and non-musicians alike. A few pills of truth in this little investigation ‘into the causes and circumstances of W. A. Mozart’s death‘.

. . . .

At the age of only 35, Mozart died in Vienna at 12:55 a.m. on 5 December 1791 but, due to the state of destitution in which he then found himself having squandered the enormous fortune he had earned from his career as a composer and concert pianist, he could not be with a dignified burial. After the funeral ceremony, Mozart’s body was buried the day after his death in a mass grave, the whereabouts of which are unknown to this day, and his remains were thus dispersed.

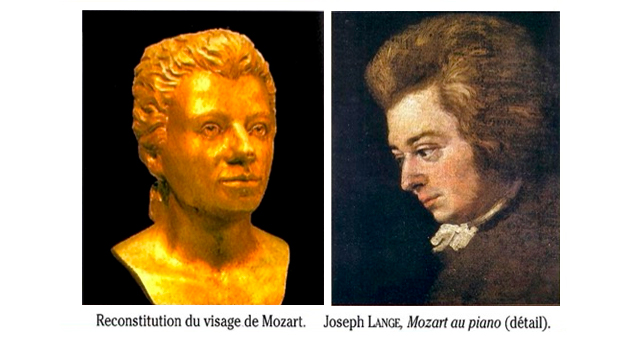

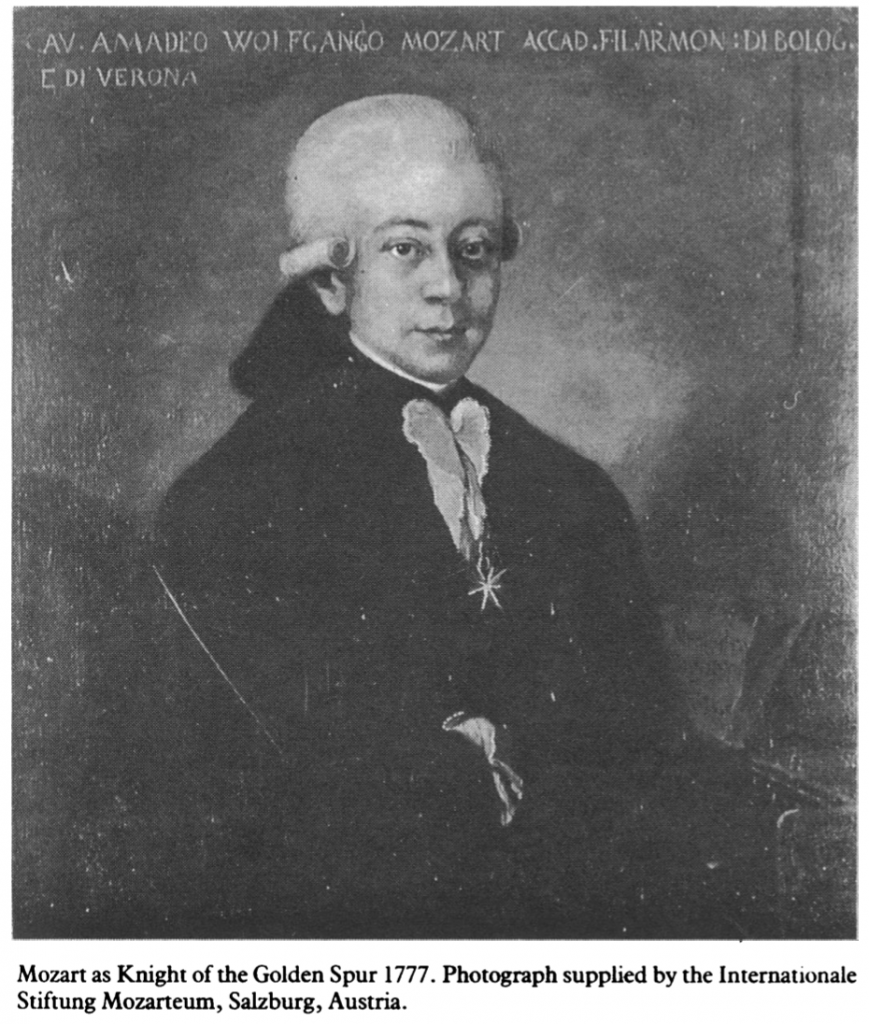

It should also be mentioned that the presumed remains of Mozart, later exhumed, were identified as belonging to the great composer, in specific studies conducted by the French anthropologist Pierre Francois Puech (Identification of the cranium of W.A. Mozart) who arrived at this deduction through procedures of superimposing the cranial image with available portraits as well as through the identification of individual characteristics represented by a premature synostosis of the metopic suture and post-traumatic changes to the skull after a fall from a horse in 1770 while in Italy.

The only official document that confirms the composer’s death is the death certificate, which traces the event back to an unspecified acute miliary fever, nor did the doctors who treated him, Dr. Closset and Dr. Sallaba, consider it useful to order an autopsy.

Since then, the lack of clear diagnostic indications as to the cause of Mozart’s death has provided fertile ground for the innumerable hypotheses that, over more than two centuries, have been formulated to explain the sudden death of a man who, especially when seen through today’s eyes, died while still very young.

The legendary conflict with Salieri immediately fuelled the idea that Mozart had died not from natural causes but from poisoning at the hands of his eternal rival. Salieri himself contributed to the suspicion in the last years of his life with a confession that was soon retracted. Various poisonous substances have been implicated in this regard, from Aqua Tofana, a poison containing arsenic, lead and belladonna berry extract, to tartar emetic (potassium tartrate) but, in the absence of objective evidence and, above all, in the unavailability of remains suitable for toxicological investigations, this interpretation has gradually lost credibility.

On the other hand, the legend of Salieri’s hatred of Mozart is really to be considered as an extraordinary literary fantasy staged in the drama ‘Mozart and Salieri‘ written by Puskin – later set to music by Rimsky-Korsakov – and in Shaffer’s equally famous play ‘Amadeus’ from which Forman’s film of the same name was adapted.

Having thus set aside the prospect of a crime that, in the collective imagination, would perhaps have been better suited to the tragic end of a historical figure of Mozart’s greatness, the only remaining prospect is that of a ‘more normal and human‘ death from a natural cause, which various authors have attempted to investigate by interpreting the different information on Mozart’s state of health handed down through the ages.

The result is an anthology of diagnoses – there are more than 140! – ranging from cardiac to urinary diseases, from infectious to congenital.

With regard to the validity of the sources, in modern times the value of the testimonies given by his wife Constance and sister-in-law, Sophie Heibel, transcribed in a biography on the composer written only in 1828 (Nissen G. Life of Mozart) has been progressively downgraded, while the information contained in the copious correspondence exchanged between members of the Mozart family has gained increasing recognition (Andersen E. The letters of Mozart and his family). It should be remembered that, having immediately realized his son’s musical genius, his father Leopold ensured that he was able to perform, from a very young age, in the courts of Austria and Europe and, through the letters, the Mozart family shared both news of their prodigy son’s career and of the health problems that greatly worried the society of the time, exposed as it was to serious endemic and epidemic diseases.

It is therefore not surprising that, precisely through the description of the symptoms contained in the letters that family members exchanged over time, it has been possible to reconstruct the medical history of Mozart’s entire life.

Already at the age of only 6, Mozart fell ill with erythema nodosum and a few years later the symptoms of tonsillitis and peritonsillar abscesses were described. In 1765, the young Mozart and his sister were struck by a typhoid-like illness, endemic in 1700s Europe. This was followed by fever and joint pains, suggestive of rheumatic fever, and a mild form of smallpox that left some small scars on his face. Mozart’s health was good until 1784 when he was struck by an acute condition characterized by vomiting, colic and profuse sweating (renal colic?).

But the fateful year for Mozart was 1790. Weighed down by debts resulting from the improper management of his earnings and worried about his wife’s health, Mozart began to show signs of what was then known as ‘melancholia’, constantly complaining of headaches and toothaches (dental abscesses?).

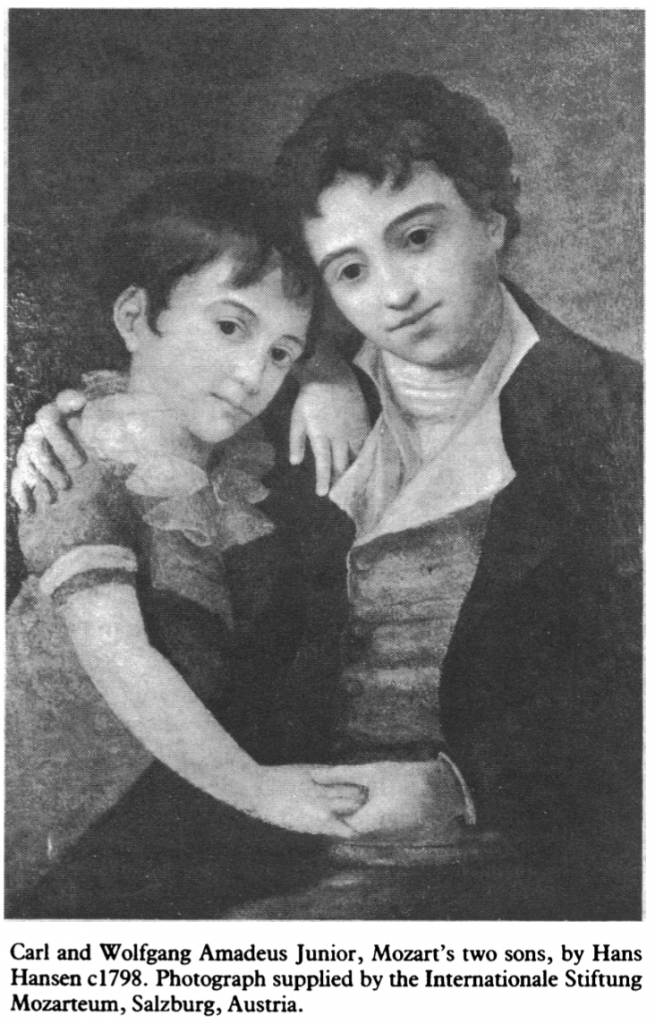

It was from this moment that, according to some authors, the psycho-physical decline that led to the musician’s death at the end of the following year began. Referring back to episodes in his youth, some of which were attributable to attacks of acute streptococcal rheumatic fever, several specialists considered that Mozart’s health was undermined by a pattern of post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis that evolved towards renal failure over the years. Mozart’s impaired renal function was indeed a diagnosis that has gained the most consensus over time, albeit with differing etiopathogenic perspectives. These include the hypothesis of a possible correlation between renal dysfunction and the altered conformation of Mozart’s auricle in the context of a congenital syndrome, also supported by the fact that the same auricular alteration was later documented in the composer’s eldest son.

. published in the British Medical Journal in 1986, which we show below.

All of this results, even if not very clearly, from some of the pictures in the paper by Paton et all. published in the British Medical Journal in 1986, which we show below.

Nevertheless, what is unconvincing about the suggestion of a chronic pathology is the persistent creative vitality manifested by the composer still in the last months of his life, which is hardly reconcilable with a progressive psycho-organic deterioration, whereas it better corresponds to a sudden acute pathological event with a rapid exacerbating development.

Which version is more reliable? Was it a chronic illness or an acute event?

Further analysis of the correspondence and chronicles of the time yields the following indications about the last period of Mozart’s life:

- July 1791: in one letter he explicitly wrote that he was quite well;

- 8 and 9 October 1791: in letters sent to his wife Mozart was elated by the quality of the food provided for his dinner, thus denoting an appetite and taste for food;

- on the evening of 9 October he attended a performance of the Magic Flute and he joked with the singer who played Papagheno by playing a few chimes from behind the scenes at a moment of absolute silence in the opera;

- in the following days’ letters he repeatedly recalled the pleasure of food, confirming a healthy appetite. He also showed himself to be a planner by talking about the future of his eldest son;

- In the last months Mozart’s work also remained powerful: he composed La Clemenza di Tito for the coronation of Emperor Leopold II in the incredibly short interval of only 18 days.

- It was only on his return to Vienna, after a stay in Prague, that his health took a real turn for the worse.

- On 18 November 1791 Mozart conducted his last work, La piccolo cantata massonica, completed on 15 November, and this was his last public outing.

- From 20 November 1791 Mozart was bedridden due to a painful swelling of his limbs (oedema), which made it impossible for him to even move in bed, accompanied by profuse sweating, vomiting and burning fever. The attending physicians also reported the appearance of skin rashes.

Mozart died only 15 days after the onset of symptoms.

A few years later, in a correspondence of his own with a colleague, Dr. Closset wrote that Mozart had fallen ill at the end of the autumn with rheumatic fever, an illness that had affected many inhabitants of Vienna at that time and, for many, as for Mozart, with a fatal outcome.

Taking up Dr. Closset’s suggestion and shifting the perspective of observation to the epidemiological level, it must be said that in 18th century Europe, the average age of death was 35 (several of Mozart’s acquaintances died around that age) and the main causes of death were infectious diseases (typhus, typhoid fever, smallpox, scarlet fever).

With reference to Vienna, the city where Mozart fell ill and died, the register of causes of death for the period between the end of 1791 and 1793 shows the deaths of 5011 adults (3442 men and 1569 women), with an average age of 45.5 for males and 54.5 for women. The first cause of death at that time was tuberculosis, then cachexia and malnutrition and, in third place, oedema. This last pathological picture, and the related deaths, increased significantly in the younger male population precisely between the end of November and the beginning of December 1791, and the origin of this ‘outbreak’ was referred to the local military hospital.

All these elements end up contextualizing Mozart’s death in an acute epidemic pathological context consistent with his clinical picture and which caused the death of many people, like Mozart, while still young.

Placed in the context of the time, Mozart’s death thus does not appear to differ from that of many of his contemporaries, and the aura of mystery it has always romantically evoked is thus dispelled.

Also because, apart from the suspicion of murder, once again a literary genius – in this case we are talking about Stendhal – fueled the dramatic aspect of the end of Mozart’s existence linked to his last composition, the Requiem, which remained, as we know, unfinished in its last part. Mozart, according to the great French writer inhis book ‘Lives of Haydin, Mozart and Metastasio‘, was convinced that the mysterious commissioner of the composition came from beyond and that the mass he was writing, therefore, was the one that was to celebrate his funeral. In reality, the commissioner was anything but mysterious: he was Count Franz Graf von Walsegg, an amateur musician who often paid composers to produce music that he then passed off as his own. In this case, the Requiem Mass would have served to commemorate the count’s wife who had recently passed away.

Mysteries aside, the regret remains for the early demise of Mozart’s genius who, although he had already had the time and opportunity to change the history of western music, still possessed a powerful creative power that could not be fully expressed.

And beyond the literary imagination remains, at least for fans, the powerful image that Forman offers us in his film Amadeus of the great feverish composer on his deathbed composing, with the ease that distinguished him, the powerful notes of Confutatis (Confutatis maledictis, Flammis acribus addictis, Voca me cum benedictis) that transport Mozart, and us with him, from the flames of damnation to the light of salvation.

.

Read also: 5 maggio 1821-2021. Nel bicentenario della morte di Napoleone una revisione della sua autopsia